Multiple Sclerosis

- related: Neurology

- tags: #neurology

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disorder of the central nervous system (CNS) that causes inflammatory damage to the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerve. Most of the overt clinical symptoms of MS occur as a direct consequence of functional interruption of critical axonal pathways by inflammatory lesions. Relapses or flares involve development of neurologic symptoms over the course of hours to days and often peak in severity over the course of days to weeks. This is typically followed by a period of remission lasting weeks to months. Remyelination and recruitment of other brain regions to functionally substitute for the damaged area may result in clinical improvement during times of remission.

The most common clinical manifestations of MS are optic neuritis, myelitis, and brainstem/cerebellar syndromes.

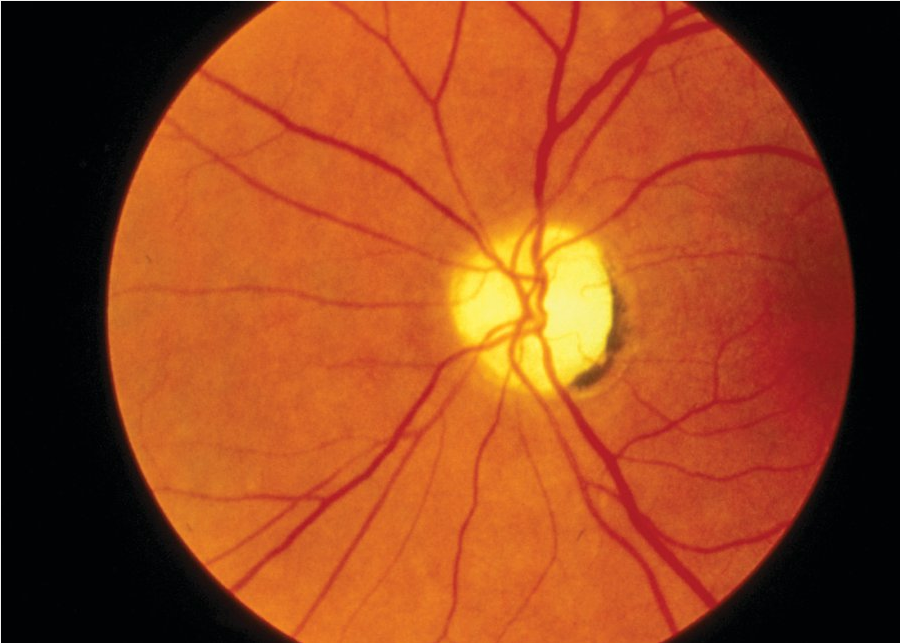

Patients with optic neuritis typically have subacute visual deficits in one eye that are occasionally associated with pain with eye movement and/or flashing lights (photopsia). Formal ophthalmologic examination shows a reduction in visual acuity, a scotoma or visual field deficit, difficulty with color discrimination, and an afferent pupillary defect. Papillitis (flared appearance of the optic disc caused by inflammatory changes; Figure 22) can sometimes be seen, although this finding only occurs with involvement of the head of the nerve. Optic disc pallor (Figure 23) is usually seen as a late consequence of optic neuritis and is secondary to atrophy of the optic nerve.

Optic nerve papillitis is characterized by hyperemia and swelling of the disk, blurring of disk margins, and distended veins. Papillitis is seen in one-third of patients with optic neuritis.

Optic nerve papillitis is characterized by hyperemia and swelling of the disk, blurring of disk margins, and distended veins. Papillitis is seen in one-third of patients with optic neuritis.

A pale, flat optic disk characteristic of optic nerve atrophy.

A pale, flat optic disk characteristic of optic nerve atrophy.

Brainstem syndromes often involve pathways for eye movement and result in diplopia or oscillopsia (a sensation of jerking of the visual field). Examination may reveal dysconjugate eye movements, nystagmus, and/or internuclear ophthalmoplegia (inability to adduct one eye and nystagmus in the abducting eye).

Spinal cord involvement or myelitis results in sensory and/or motor symptoms below the affected spinal level. Unlike other spinal cord processes, MS generally causes a partial myelitis, and symptoms of full-cord transection are rare; crossed sensory-motor symptoms may also occur (as in partial Brown-Séquard syndrome). Neurologic examination generally reveals focal weakness and/or reduced sensation below a specific spinal dermatome. Muscle tone can be reduced acutely, whereas spasticity and hyperreflexia often are delayed findings. During acute inflammation, some patients will also experience a tight, band-like sensation around the body involving the affected spinal level (“MS hug”). Lhermitte sign, which also can occur with upper cervical cord lesions from other causes, manifests as a shock-like sensation radiating down the spine or limbs with flexion of the neck. Urinary frequency, urgency, hesitancy, or retention also may be seen.

Disruption of vestibular or cerebellar pathways may result in ataxia and/or vertigo. Neurologic examination will reveal appendicular or truncal ataxia, dysmetria on finger-to-nose testing, difficulty with rapid alternating movements, and impairment of tandem gait.

Most patients with MS also develop subtle, chronic symptoms that occur as a consequence of more widespread cortical demyelination and nonlesional axonal pathology. At least 50% of patients with MS experience cognitive deficits, typically in domains of short-term memory, visuospatial function, and processing speed. Many patients with MS also report fatigue, which can manifest as a feeling of exhaustion despite adequate sleep, a feeling of brain fog, and easy physical fatigability.

Many patients with MS also experience Uhthoff phenomenon, a transient worsening of baseline neurologic symptoms in the setting of hot weather, physical exertion, or fever. This worsening occurs because of a temporary reduction in neuronal electrical conductance at higher temperatures, which causes magnification of symptoms from previously demyelinated pathways. Any patient with a suspected relapse should be screened for causes of Uhthoff phenomenon masquerading as a relapse (or “pseudorelapse”) to avoid unnecessary treatment. Patients often need reassurance and counseling that such events are not indicative of new inflammatory damage.

Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis

Diagnostic Criteria and Testing

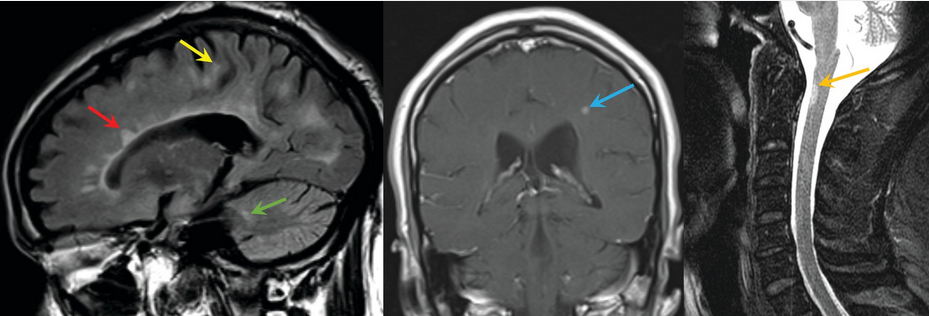

Because no specific genetic or serologic diagnostic biomarker is available for diagnosing MS, the diagnosis is made through rigorous application of diagnostic criteria that integrate clinical and radiologic findings. The McDonald criteria require symptoms of CNS demyelination separated in space and time from a series of clinical relapses or progression, signs on physical examination, distribution of lesions on MRI, and (if necessary) the presence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-unique oligoclonal bands. Proper application of the diagnostic criteria can prevent unnecessary neurologic testing, referrals, and misdiagnoses. A standardized MRI brain protocol should be used for all diagnostic evaluations of potential MS. Spinal cord imaging also should be performed in patients with symptoms of myelitis, patients with insufficient features on a brain MRI to support the diagnosis, and patients older than 40 years with nonspecific brain MRI findings. Strict adherence to the McDonald criteria for MS-specific lesions is critical because many other disorders (migraine, head trauma, and cerebrovascular disease) also can cause brain (but not spinal) lesions on MRI. Figure 24 shows examples of periventricular, juxtacortical, and infratentorial lesions that are specific to MS and satisfy the McDonald criteria; if visible, lesions in the cortex may substitute for juxtacortical lesions, according to the official diagnostic criteria. Ancillary testing can show objective clinical evidence of a demyelinating lesion. Demyelinating lesions of the optic nerve can be electrophysiologically confirmed with visual evoked potentials. Optic coherence tomography, which uses near-infrared light to quantify the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer and macula, also can confirm optic nerve damage in acute or previous optic neuritis. Conductance delay in brainstem auditory evoked potentials and somatosensory evoked potentials can act as surrogate markers of demyelination in brainstem and spinal cord pathways. Despite the usefulness of such testing for determining anatomic localization, however, MRI is the only objective measure that fulfills the diagnostic criteria.

Left, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery brain MRI that shows periventricular (red arrow), juxtacortical (yellow arrow), and infratentorial (green arrow) lesions specific to multiple sclerosis (MS); if visible, lesions in the cortex can substitute for juxtacortical lesions, according to official diagnostic criteria. Middle, coronal T1-weighted postcontrast MRI of the brain showing a contrast-enhancing MS lesion (blue arrow). Right, sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the spinal cord showing an MS lesion (gold arrow).

Left, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery brain MRI that shows periventricular (red arrow), juxtacortical (yellow arrow), and infratentorial (green arrow) lesions specific to multiple sclerosis (MS); if visible, lesions in the cortex can substitute for juxtacortical lesions, according to official diagnostic criteria. Middle, coronal T1-weighted postcontrast MRI of the brain showing a contrast-enhancing MS lesion (blue arrow). Right, sagittal T2-weighted MRI of the spinal cord showing an MS lesion (gold arrow).

CSF testing is not required for a diagnosis of MS if the McDonald criteria are otherwise met. However, CSF findings can be used to support the diagnosis when the MRI criteria are not fully met. The normally functioning blood-brain barrier excludes immunoglobulins from the CSF in healthy persons, which results in a blood to CSF IgG ratio of 500:1 or greater. Oligoclonal bands indicate elevations in oligoclonal immunoglobulin concentrations in the CSF and may result from disruption of the blood-brain barrier or intrathecal production of IgG. The presence of oligoclonal bands in the CSF that are absent in the serum occurs in 85% to 90% of persons with MS. An elevated IgG blood-to-CSF index and an elevated IgG synthesis rate also are possible. Nonspecific mild elevations in the CSF leukocyte count or protein level are sometimes seen.

Differential Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis

Knowledge of the various rheumatologic, inflammatory, infectious, and metabolic disorders with the potential to mimic the clinical signs/symptoms and radiologic changes of MS is important when considering the diagnosis (Table 42).

Clinical Course of Multiple Sclerosis

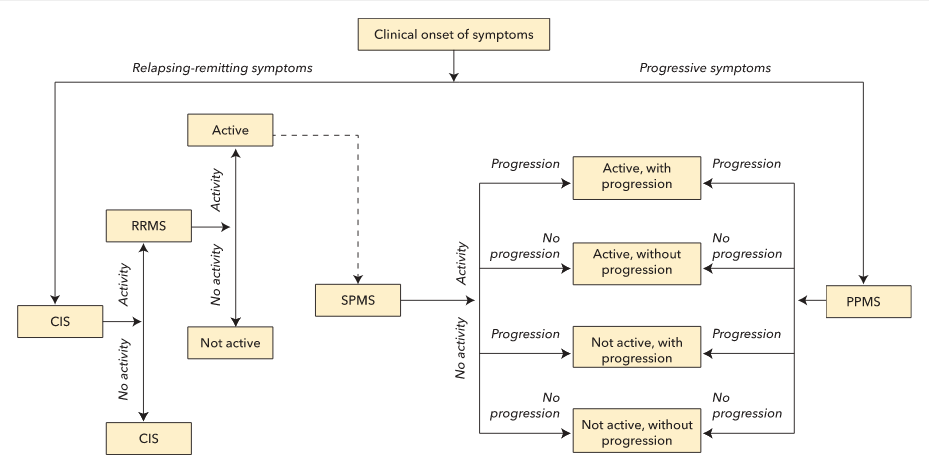

The clinical phenotypic definitions of MS recently have been modified to acknowledge that manifestations of MS are heterogeneous and can evolve over time (Figure 25). Approximately 85% of patients with MS experience an initial relapsing-remitting course. Those with a first demyelinating event that does not meet the definition of clinically definite MS are said to have a clinically isolated syndrome. Any future disease activity, defined as a clinical relapse or a new or contrast-enhancing lesion on MRI, results in conversion to a diagnosis of clinically definite relapsing-remitting MS. Because disease-modifying therapies reduce the risk of conversion from a clinically isolated syndrome to relapsing-remitting MS by approximately 50%, stratification of risk for conversion can inform treatment decisions. Patients with brain lesions on MRI at the time of their clinically isolated syndrome have a 10-year risk of conversion to relapsing-remitting MS of approximately 90%, whereas patients without brain lesions have a much lower risk (10%–20%).

At clinical onset, multiple sclerosis (MS) can be either relapsing or progressive in nature. An initial, isolated demyelinating event results in a preliminary diagnosis of a clinically isolated syndrome. Any further activity (defined as a clinical relapse, new or enlarging T2-weighted lesion on MRI, or gadolinium-enhancing lesion on MRI) results in a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). Over time, RRMS can either be classified as active (if evidence of activity exists) or not active. Some patients with RRMS can later exhibit signs of progression (defined as slowly progressive accumulation of disability), and their condition can be reclassified as secondary progressive MS (SPMS). An initial clinical onset of progressive, nonrelapsing symptoms is diagnosed as primary progressive MS (PPMS). Any patients with progressive MS (PPMS or SPMS) can later exhibit signs of activity and/or progression, which allows for further stratification into four categories based on the presence or absence of these qualities.

At clinical onset, multiple sclerosis (MS) can be either relapsing or progressive in nature. An initial, isolated demyelinating event results in a preliminary diagnosis of a clinically isolated syndrome. Any further activity (defined as a clinical relapse, new or enlarging T2-weighted lesion on MRI, or gadolinium-enhancing lesion on MRI) results in a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). Over time, RRMS can either be classified as active (if evidence of activity exists) or not active. Some patients with RRMS can later exhibit signs of progression (defined as slowly progressive accumulation of disability), and their condition can be reclassified as secondary progressive MS (SPMS). An initial clinical onset of progressive, nonrelapsing symptoms is diagnosed as primary progressive MS (PPMS). Any patients with progressive MS (PPMS or SPMS) can later exhibit signs of activity and/or progression, which allows for further stratification into four categories based on the presence or absence of these qualities.

CIS = clinically isolated syndrome; MS = multiple sclerosis; PPMS = primary progressive MS; RRMS = relapsing-remitting MS; SPMS = secondary progressive MS.

Determination of activity status may also inform treatment decisions in relapsing-remitting MS. In the first few years that a patient has this type of MS, significant or complete recovery from relapse is common. Over time, however, postrelapse recovery generally diminishes, and permanent disability accumulates. Without treatment, half of patients with relapsing-remitting MS develop secondary progressive MS after a median of 10 to 15 years. Data now suggest that the introduction of disease-modifying therapies has decreased the proportion of patients converting to secondary progressive MS. In secondary progressive MS, relapses become infrequent or cease completely, but slowly progressive neurologic disability continues to accrue in multiple domains.

Approximately 15% of patients with MS have primary progressive MS at presentation. This subtype often develops later in life (in the fifth or sixth decade) compared with the younger age of onset (third or fourth decade of life) in typical relapsing-remitting MS. Because patients with both primary and secondary progressive MS can have periods of disability progression or stability (with some even having permanent halting of progression), adding the modifiers “with progression” and “without progression” to these diagnostic terms has been suggested. Occasionally, patients with these types of MS may meet criteria for relapsing activity (clinical relapses, new or contrast-enhancing lesions on MRI) and thus can be further stratified into “active” and “not active” categories.

Patients with a radiologically isolated syndrome have no clinical symptoms of MS but are found incidentally to have MRI findings that meet the radiologic criteria for MS. Although an MS diagnosis cannot be made in the absence of demyelinating signs and symptoms, it has been shown that patients with a radiologically isolated syndrome are at high risk for later conversion to clinically definite MS and should be monitored closely.

Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis

Lifestyle Modifications and General Health Care

Although some patients with MS may avoid physical activity because of disability, fatigue, and the Uhthoff phenomenon, repeated studies have shown multiple benefits from both strengthening and aerobic exercise programs. Patients with significant Uhthoff phenomenon induced by exercise should be reassured that neurologic injury will not result from exercise; they also can be counseled on strategies to minimize discomfort, such as heat avoidance or external cooling (cold water, fans, body-cooling devices) during exercise.

Exercise also can help preserve bone health. Patients with MS have a three- to sixfold increased risk of reduced bone mineral density, most likely from a combination of reduced physical activity, repeated use of glucocorticoids, and vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D deficiency is common in MS patients, and reduced serum levels of vitamin D are predictive of MS development and future accumulation of lesions on MRI. A randomized trial of vitamin D supplementation added to interferon beta treatment resulted in reduced accumulation of lesions seen on MRI compared with placebo. Vitamin D supplementation is now recommended for all patients, although the ideal dosing regimen and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level are still being investigated.

Measures to prevent infection are needed for patients receiving more aggressive, immunosuppressive MS treatments, especially given the increased risk of MS relapse at the time of systemic infection. Current MS treatment guidelines recommend vaccination against influenza (with inactivated vaccine) and maintenance of standard immunizations. Immunizations should be withheld during MS relapses. All live vaccines are contraindicated in patients receiving immunosuppressant or immunomodulating therapies. Patients with MS-related bladder dysfunction are at higher risk of recurrent urinary tract infection, and thus strategies to reduce the frequency of bladder infections are necessary.

Smoking cessation is advised for all patients with MS because of the threefold risk of conversion from relapsing-remitting MS to secondary progressive MS and faster rates of disability accumulation in cigarette smokers.

Many patients with MS are women in their childbearing years. The estrogenic state of pregnancy has an immunomodulatory effect that tends to reduce MS disease activity during pregnancy, often precluding the need for treatment during this period. Although the risk of relapse is increased slightly in the first 3 months of pregnancy, this does not seem to contribute negatively to prognosis; multiple studies have shown that pregnancy does not result in additional permanent disability and that multiparous women have better long-term MS outcomes than nulliparous or uniparous women. Data on the effect of breastfeeding on MS relapse risk are inconclusive.

Treatment of Acute Exacerbations

An MS relapse is defined as new or worsening neurologic symptoms lasting more than 24 hours. Symptoms lasting only minutes to hours should not be considered or treated as a relapse. The possibility of a pseudorelapse should always be considered before initiating treatment; suspicion of this condition should trigger clinical investigation for an underlying cause. The subsequent treatment of any infection or metabolic disturbance often results in improvement in neurologic symptoms.

The standard treatment for MS relapses is high-dose glucocorticoids, typically intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g/d for 3 to 5 days). Multiple trials have shown that bioequivalent doses of oral glucocorticoids (such as prednisone, 1250 mg/d) are equally effective and well tolerated, with reduced cost. Because of their ease of administration and reduced costs, high-dose oral regimens are beginning to replace intravenous methylprednisolone, although either approach is valid. Adverse effects of high-dose glucocorticoids include insomnia, hyperglycemia, metallic taste, gastritis, fluid retention, irritability, and (rarely) psychosis. These effects are typically short lived, given the brief duration of treatment. Frequent or prolonged glucocorticoid treatment should be avoided to minimize the risks of osteopenia and early cataracts.

MS relapses also can be treated with administration of a short course of intramuscular adrenocorticotropin hormone gel. This approach has a more favorable adverse-effect profile compared with external glucocorticoid administration. Use of this gel is limited by prohibitive pricing.

Patients not responding to glucocorticoid treatment may respond to plasmapheresis, administered as five consecutive exchanges.

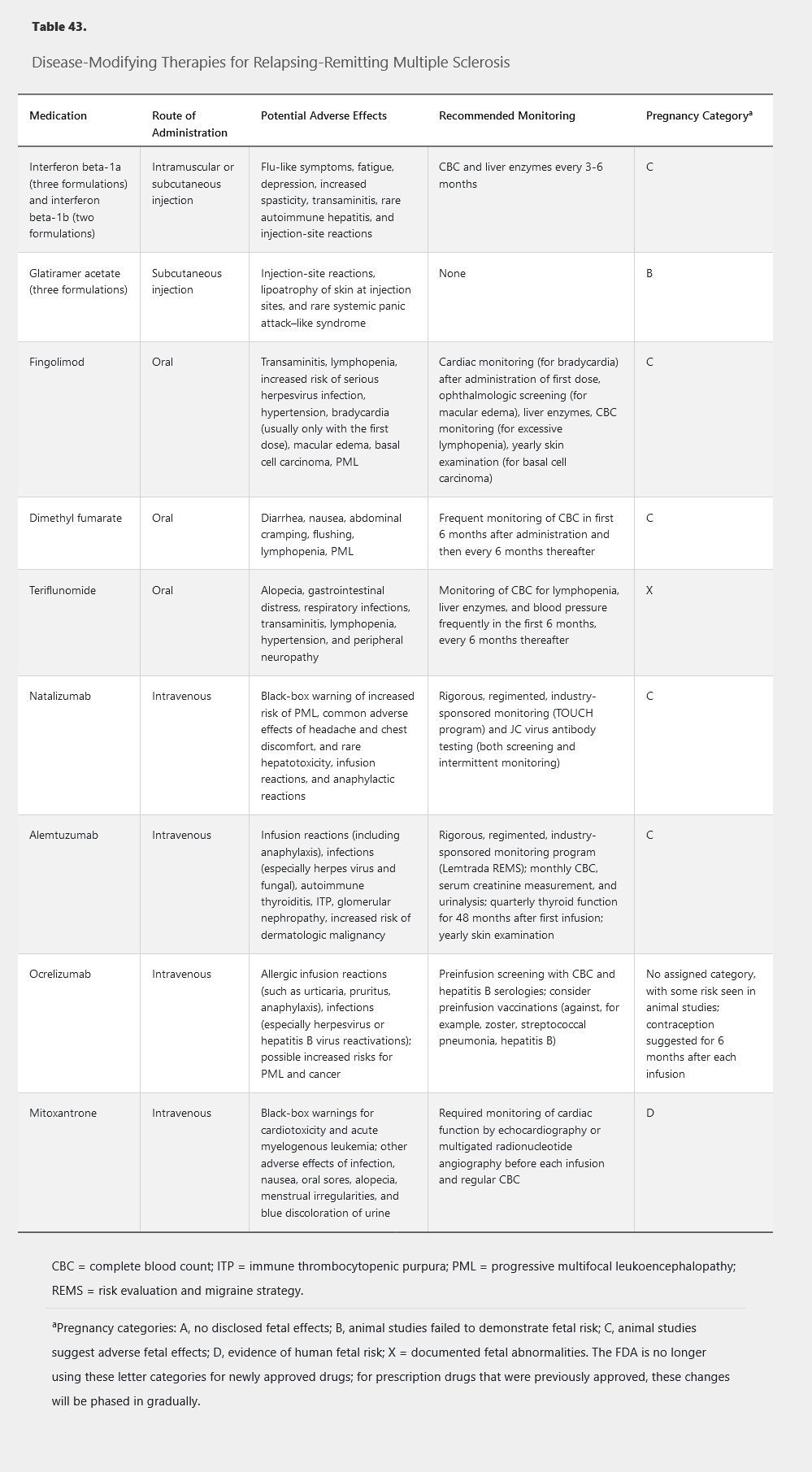

Disease-Modifying Therapies

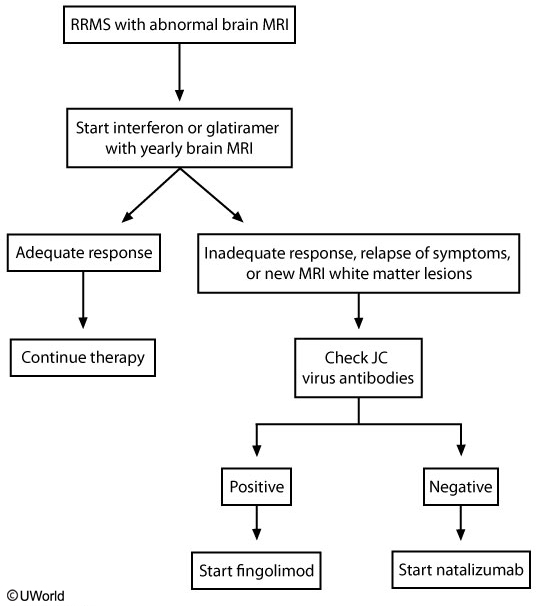

Prevention of MS relapse is vital. Various immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive medications have been shown to reduce the risk of relapse, disability progression, and new MRI lesion formation. Currently, many disease-modifying therapies are approved and available for use in relapsing-remitting MS (Table 43), each differing in its route of administration, mechanism of action, and potential adverse effects. Interferon beta preparations, glatiramer acetate, and teriflunomide have additional utility in clinically isolated syndrome for prevention of conversion to clinically definite MS. Despite many options for those with relapsing disease, the options for patients with progressive forms of MS are limited. Mitoxantrone is currently the only FDA-approved therapy for secondary progressive MS, and ocrelizumab is the only FDA-approved therapy for primary progressive MS. Clinical trials of interferon beta, glatiramer acetate, fingolimod, and natalizumab in progressive forms of MS have failed to show benefit, and thus prescribing these medications in progressive MS not only increases cost but burdens patients with unnecessary adverse effects.

Selection of an appropriate disease-modifying therapy involves consideration of comorbidities, patient tolerability, risk stratification, and disease activity. Treatment decisions often are made in consultation with a neurologist or MS specialist. There is no clear consensus about how to select the appropriate therapy, what defines treatment failure, or how to decide in what order medications should be introduced. Generally, most physicians recommend self-injection medications (an interferon beta or glatiramer acetate) as first-line agents, given their favorable risk profiles. Patients who exhibit disease breakthrough on these medications or who are unable to tolerate their adverse effects are often switched to agents with better efficacy profiles. Although the oral therapies and monoclonal antibodies provide greater efficacy, they are associated with greater risk and the need for more intensive monitoring.

Interferon beta (available as interferon beta-1a and interferon beta-1b) is an immunomodulatory cytokine treatment that shifts immune responses away from autoimmunity and increase the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. Interferons beta-1a and beta-1b are available in multiple formulations and are administered via subcutaneous or intramuscular injection on schedules varying from every other day to twice monthly. They reduce relapse rates by approximately one-third compared with placebo and have positive effects on disability progression and MRI findings. Head-to-head studies show general equivalence of the formulations, although those requiring frequent injections have slightly higher efficacy in some studies. Interferon beta may exacerbate depression, and care should be taken when administering it to patients with a history of psychiatric disease.

Glatiramer acetate exerts its immunomodulatory effect through modification of the nonbinding sites of major histocompatibility complex molecules. Structurally similar to myelin basic protein, it also may work through molecular mimicry. Glatiramer acetate is available for daily or three times weekly subcutaneous injection. Reduction in relapse rates is similar to that of the interferon beta formulations. Combining glatiramer acetate with interferon beta provides no added benefit.

Fingolimod is an oral agent that results in sequestration of activated lymphocytes within lymph nodes. Fingolimod reduces relapse rates by approximately one-half compared with placebo and also reduces the risk of disability progression and the development of new MRI lesions. However, intensive monitoring is mandatory with fingolimod because of its rare adverse effects, including infection and heart block.

Dimethyl fumarate is an oral agent that activates the nuclear factor–like 2 transcriptional pathway and results in immunomodulation. It reduces relapse rates by slightly less than half and reduces the risk of disability progression and MRI lesion development. Infectious risks of dimethyl fumarate correlate with prolonged lymphopenia, and frequent blood-count monitoring is required.

Teriflunomide is an oral medication that inhibits a mitochondrial enzyme involved in pyrimidine synthesis in rapidly dividing cells. This drug reduces relapse rates by a third compared with placebo and also reduces the risk of disability progression and new MRI lesion development. Dual-method contraception is recommended with teriflunomide because of its known teratogenic effects.

Natalizumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting a cellular adhesion molecule on activated T-cells required for transmigration into the CNS. Administered intravenously once monthly, natalizumab is a highly effective treatment, resulting in a two-thirds reduction in relapse rates, slowing of disability progression by approximately 40%, and a reduction in MRI activity of approximately 90% compared with placebo. Despite this high efficacy, natalizumab is typically limited to use as a second-line agent because of the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a CNS demyelinating infection caused by reactivation of the JC virus. Duration of treatment, seropositivity for the JC virus, and previous exposure to chemotherapy or immunosuppressants increase PML risk. PML is uncommon in time-limited treatment in patients without other risk factors.

Alemtuzumab is an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody that causes complement-mediated lysis of circulating lymphocytes. It is administered as an intravenous infusion with an initial course of once daily for 5 days, followed by 3 consecutive days 1 year later. Alemtuzumab reduces relapse rates and disability progression by approximately half and reduces new lesions and brain atrophy on MRI compared with interferon beta. Despite high efficacy, use of this drug also is limited due to significant safety concerns (see Table 43), all of which require intensive safety monitoring and potential prophylaxis.

Ocrelizumab is a monoclonal antibody against the CD20 antigen that causes lysis of circulating B cells. This drug is administered through intravenous infusion, initially as two infusions 2 weeks apart followed by a one-time infusion every 6 months. Ocrelizumab is the first medication to show benefit for patients with both relapsing-remitting MS (reductions in relapse rates, MRI disease burden, and disability accumulation) and primary progressive MS (reduced chance of disability progression). Safety concerns include allergic infusion reactions and increased risk for treatment-related infections.

Mitoxantrone is an anthracenedione chemotherapy drug that exerts an immunosuppressive effect by reducing lymphocyte proliferation. Although mitoxantrone is highly effective for relapsing-remitting MS and is the only drug approved for use in secondary progressive MS, it has fallen out of favor given its significant risks of cardiac toxicity and treatment-related leukemia.

Symptomatic Management

Despite the use of disease-modifying therapies, many patients still experience both chronic and intermittent neurologic symptoms. Proper management of these symptoms with pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches can increase quality of life for patients with MS.

MS spasticity is due to corticospinal tract damage, resulting in increased muscle tone, painful muscle cramps, spasms, and contractures. The use of muscle relaxants, such as baclofen, tizanidine, cyclobenzaprine, and the benzodiazepines may be helpful. Gabapentin, medical marijuana, synthetic tetrahydrocannabinol compounds, and cannabis extract are beneficial in reducing painful spasms. Strategic use of botulinum toxin and intrathecal baclofen pumps may help in patients whose disease is refractory to oral therapies. Physical therapy, stretching, and massage therapy can be used as nonpharmacologic alternatives or additions to therapy.

Neuropathic pain is a common MS-related symptom and can be addressed with many of the same pharmacologic agents used to treat painful diabetic neuropathy (see MKSAP 18 Endocrinology and Metabolism). Nonpharmacologic approaches, such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, also can be integrated into the management plan.

Chronic fatigue is a common and life-impairing symptom in MS. Although fatigue is sometimes related to concurrent depression, insomnia, or other comorbid conditions, patients with MS without any of these issues also can experience disabling fatigue. Improved sleep hygiene, regular exercise, and treatment of underlying depression can be beneficial. For those with refractory fatigue, stimulant medications can be used. The most common medications of this type used (off-label) in MS are modafinil, armodafinil, and amantadine. For fatigue that is refractory to these medications, amphetamine stimulants, such as methylphenidate, also can be considered. Complementary and alternative medicine approaches, such as magnetic therapy and ginkgo biloba, also have shown efficacy in some studies.

Depression is far more common in MS patients than in those without the disorder. Furthermore, the suicide rate for patients with MS and depression is elevated compared with that of patients with depression only. MS-related depression is likely multifactorial, involving the emotional response to dealing with a chronic disease, the consequence of demyelinating lesions and inflammatory cytokines on neurotransmitter function, and the adverse effects of treatments (such as interferon beta). Clinicians should be vigilant for the signs of depression, screen for suicidality if present, and have a low threshold for initiating antidepressants and offering referrals to psychiatry or psychology for counseling.

Cognitive dysfunction occurs in at least half of patients with MS, affecting employability and quality of life. Typical findings include deficits in short-term memory and processing speed, although almost any domain can be impaired. Trials of pharmacologic therapy, such as memantine, donepezil, and methylphenidate, have not shown efficacy. Exercise, formal neuropsychological testing, and cognitive rehabilitative and accommodative strategies (such as creating checklists to overcome memory deficits) are sometimes beneficial.

Maintenance of mobility in MS patients is essential to maintaining quality of life. An active healthy lifestyle is necessary to help stave off future disability. Physical and occupational therapy can provide gait safety training and improve balance and endurance. Assistive devices, such as braces, canes, walkers, and electrostimulatory walk-assist devices, can provide additional benefit. Pharmacologic therapy with dalfampridine, a voltage-gated potassium channel antagonist, can improve walking speed, leg strength, and gait in patients with MS and baseline gait impairment. Dalfampridine has a rare risk of seizures and should not be used in patients with known epilepsy or with kidney impairment.

Bladder dysfunction occurs in many patients with MS. Urinary frequency and urgency can be ameliorated with abstinence from caffeine, timed voids, and anticholinergic medications (solifenacin, oxybutynin, tolterodine). Patients with urinary hesitancy or retention can be more difficult to treat. Anticholinergic agents can worsen retention and increase the risk of urinary tract infection. Patients with a mixed pattern of bladder symptoms should be evaluated by a urologist; intermittent catheterization or an indwelling catheter may be necessary.

Limb tremor can occur in patients with MS and is often difficult to treat. Occupational therapy and botulinum toxin may be helpful.

Pseudobulbar affect is a rare complication of MS that can be a significant impediment to social interaction for affected patients. This symptom manifests as uncontrolled fits of laughter or crying that occur without distinct or appropriate triggers. Dextromethorphan-quinidine can help reduce this symptom.